Do you abuse your “good” days?

And pay that hefty price…

I had a good day yesterday. Actually, I had a great day. The kind where you feel almost normal, where your energy cooperates, where you think “maybe I’m getting better.”

So naturally, I tried to cram three weeks’ worth of living into 24 hours.

Big mistake.

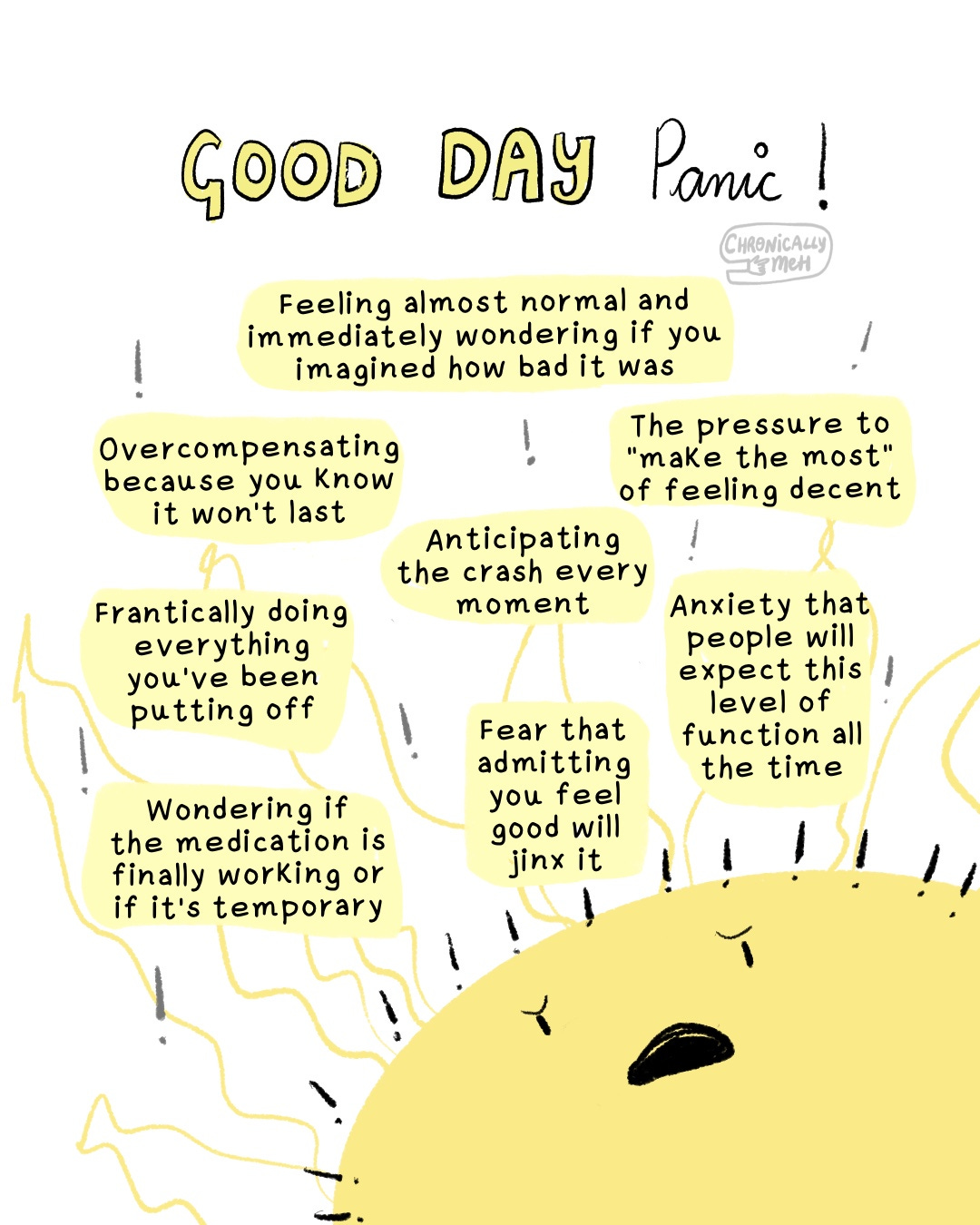

Good day panic

There’s this thing that happens when you live with chronic illness or mental health conditions — when you have a rare good day, you panic. Not because it’s bad, but because you know it won’t last.

Your brain starts calculating: “If I feel this good right now, I need to get everything done. I need to make up for all the days I couldn’t function. I need to prove I’m not as sick as I thought.”

So you overstretch. You say yes to everything. You tackle the entire backlog of tasks you’ve been putting off. You make plans, clean the house, work late, socialize, and exercise; sometimes all in the same day.

You know your limits, but you ignore them because FOMO kicks in. Fear of missing out on feeling human. Fear that if you don’t use every minute of this energy, you’re wasting it.

The crash

Then comes tomorrow. Or the day after. Or sometimes the same evening.

The crash hits like an 18-wheeler. Your body presents the bill for borrowing against future energy reserves, and the interest is brutal. You feel flattened, like in Tom & Jerry. Brain fog rolls in. Pain flares up. The simplest tasks feel impossible.

And then the spiral starts: “This is going to last forever. I’ll never feel good again. Why did I think I was getting better? I’m back to square one.”

But underneath that despair is another fear that sounds completely contradictory: “What if this crash doesn’t last forever? What if I have another good day next week and I waste it again?”

You start doing terrible math in your head. “If I only get one good day per month, I can’t afford to rest during it.” Or “I’ve been useless for two weeks, so I owe myself 14 days’ worth of productivity in this one good day.”

But bodies don’t work like bank accounts. You can’t save up energy, and you can’t make up for lost time by doubling down when you feel better. Trying to balance the books just puts you deeper in debt.

The good day wasn’t a lie or a tease. It was real. But it was also finite, and pretending otherwise just makes the crash worse.

The double fear

When you’re in the crash, you experience two opposing fears simultaneously:

“This will never end.” The exhaustion feels permanent. You forget what a good day felt like. You convince yourself you imagined the improvement.

“This will end, and I’ll waste the next good day too.” You’re already planning how to handle the next burst of energy “better,” which usually means making the same mistakes again.

Both fears keep you stuck. The first one makes you despair. The second one makes you desperate.

Learning to not blow it

The hardest lesson is learning that a good day isn’t a free pass to ignore your limitations. It’s still a day within your chronic condition, just a better one.

This means using the energy you have, not the energy you wish you had. It means doing important things, not everything. It means enjoying feeling better without trying to make up for every bad day that came before.

Sometimes the most radical thing you can do on a good day is pace yourself. Rest when you need to, even when you feel like you don’t. Save some energy for tomorrow instead of spending it all today.

The good day still has value even if you don’t maximize every minute. Actually, it has more value because you get to wake up the next day without immediately paying interest on the energy you borrowed.

How do you handle the panic of a good day? What helps you pace instead of overdo?

I can relate to every single statement in the graphic!